I am a fan of the Coffee Can Portfolio, an “Active Passive” approach to investing.

The idea is simple: You try to buy a basket of the best stocks you can and let them sit for years. You incur no costs with such a portfolio, and it is simple to manage.

You can track my stock baskets here on my Scorecard.

I recently came across Ralph Wanger, former investment manager of the Acorn Fund, which returned an amazing 16.3% CAGR from 1970-2003 (that’s a 145x in 33 years!). The S&P 500 climbed 12.1%/yr (43x) over that time.

A lot of his wisdom really resonated with me.

Here is an interview he did with Money Magazine.

Q. Why do you think you turned out to be a good investor?

A. At Acorn we had a clear philosophy — to be long-term holders of smaller companies with financial strength, entrepreneurial managers and understandable businesses — and we stuck to it. Sticking to it is key.

That makes a lot of sense to me. In 2019, one of the first articles I published was called “A Case for Investing in Small Companies”. Here’s is what I wrote:

Q. Anything else?

A. I had always thought that to be a good investor you needed to hit a lot of singles and not strike out often. I was wrong. Investing, especially in small companies, is a home-run-hitter’s game.

This really hit home. This is one of the reasons I invest in baskets of stocks rather than concentrate my portfolio at the onset. To improve the likelihood of a homerun, the more “at bats” the better. Here are some of my thoughts on Investing Homeruns, and how big they need to be.

Q. When did you learn that?

A. Late ’70s, maybe. The point is, 99% of what you do in life I classify as laundry. It’s stuff that has to be done, but you don’t do it better than anybody else, and it’s not worth much. Once in a while, though, you do something that changes your life dramatically. You decide to get married, you have a baby — or, if you’re an investor, you buy a stock that goes up twentyfold. So these rare events tend to dominate things. At Acorn, for example, I might have owned 300 stocks at any given time; most disappeared into the laundry basket. But 10 might go up many times in value, and they made all the difference.

Two important takeaways:

It’s ok to buy lots of stocks.

I often find that investors are in a rush to build concentrated portfolios. Ralph, a very successful investor, provides a great counter example. He owned 300 stocks at any given time!

Home-runs Matter - Everything else is Laundry.

I loved the laundry analogy. Although most investments won’t become profound outliers, once in a while though, we as investors can hit a home-run, and it can change our portfolio outcome dramatically.

I have spoken at length about my “Investing in Mavericks” investment approach. It is designed to benefit from home-runs, and the power law of outcomes. Of course, this doesn’t guarantee success, but it ensures we’re playing the right game.

Q. But you can’t just run out and find a stock that’s going to rise twentyfold. No one can see that clearly into the future.

A. If you’re looking for a home run — a great investment for five years or 10 years or more — then the only way to beat this enormous fog that covers the future is to identify a long-term trend that will give a particular business some sort of edge.

Q. For example?

A. A $600 PlayStation now has more computing power than you could have gotten 20 years ago for $100,000. So you don’t want to invest in the computing power itself; those prices keep dropping. You want what’s downstream from the technology. Years ago I bought International Game Technology, which took a simple microprocessor, packaged it with coin slots, called it a slot machine and sold it to casinos for $8,000. It was a great stock.

Ralph felt that for a company to become an eventual home-run, it needed to operate in an industry benefiting from a long term trend. This is a great insight. If the trend is a secular one, and will remain for a long time, there will likely be many winners that benefit from it. Just look at all the winners that have emerged from the advent of Cloud Computing.

Q. Are the principles of investing helpful elsewhere in life?

A. Being disciplined, being honest, having a set of rules and following them no matter what, thinking long term, controlling your emotions — these are all useful. But only so useful and only in part of life. You don’t want to treat your wife or your kids like an investment. I mean, you don’t want to say, “Kid, you got a D-minus in English. I’m selling you.” That doesn’t work.

I do agree that rules matter. They help when emotions get in the way. But at the same time, I personally believe that investing is a game where there are no rules. Through learning and experiences, we as investors must always be willing to change our minds. That’s how we evolve. Rules make that harder.

Perhaps instead of rules, there needs to be an investment checklist or philosophy to fall back on when making decisions. One of the reasons I started writing this newsletter is to better codify my thinking about investing. I have always believed that approaching stocks like Venture Capital can beat the market. It is a philosophical lens through which I choose to view the market. Of course, it’s not fool-proof and it will evolve over time.

Final Remarks

Let’s conclude with my favorite excerpt from of the interview, when Ralph asked the interviewer the following question:

A. How many home runs did Babe Ruth hit in his best year?

Q. Sixty, in 1927.

A. How many times did he strike out that year?

Q. Darn, I used to know that. I think it was…

A. Why don’t you know?

Q. Uh, because when you hit that many home runs, it doesn’t matter how many times you strike out.

A. Exactly. You’re a great straight man.

Q. Thanks. So how many times did Babe Ruth strike out?

A. Don’t know. Not interested.

It’s the winners that count. You want to have big positions in your winners, and the losers are trivial, eventually.

The biggest takeaway:

It didn’t matter how many times Babe Ruth struck out.

Only the home-runs mattered.

Similarly, it doesn’t matter how many of your stock picks turn out to be duds. What matters are the multi-baggers.

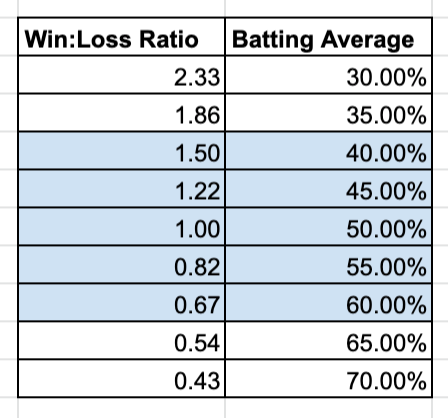

This takes me back to the following table that I shared when I wrote “Many Bets, A Few Big Payoffs”. Given a specific batting average (i.e. percent of winning investments), it shows us what “Win to Loss ratio” is required to break even.

For example, if only 45% of your investments make a profit, as long as these winning investments make at least 22% more than the average losing investment, you break even. With such stats, it means that you could be wrong the majority of the time and still break even!

Of course, the table above simply shows us the minimum bar.

By searching for home-runs, you can afford yourself a lower batting average and still come out ahead.

So next time you’re buying a stock, ask yourself, can this stock eventually become a home-run? If not, why buy it?

If you enjoyed this article, share it with a friend, they may like it too!

Thank you and Happy Investing!

ThankYou! this article gave me a something new to think about.