First, a very Happy New Year!

Second, thank you so much for having subscribed to my emails. I truly appreciate it. A special thank you to those who have connected with me. It has been great speaking with and exchanging ideas with you.

Third, I’d like to wish you and your families a wonderful, safe and happy year ahead.

Let’s Begin.

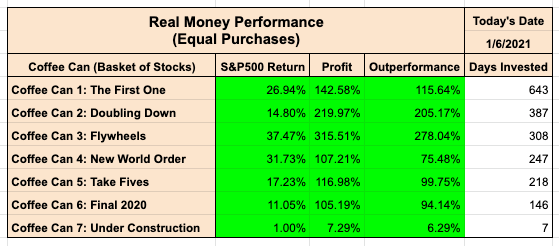

I firmly believe that if one really wants to get good at something, one needs to be keeping score. This allows for the creation of a learning system that lets us experiment, observe, iterate, and improve. This is why I keep a Scorecard.

2020 turned out to be a great year for my Investing in Mavericks investment approach. Of course, that doesn’t mean every year will be like this. In fact, it likely won’t. So one shouldn’t expect it.

With that said, it’s been 643 days since I first started sharing my Stock Baskets (Coffee Cans). I certainly didn’t expect this hit-rate. For now, I’ll take it, but only time will tell whether these were good investments. Recall, unless I see a drastic change in their underlying businesses, each of these Coffee Cans are expected to be held for at least 3-5 years.

Today, I’d like to opine about portfolio composition.

Earlier, when I wrote Investing Homeruns: How big do they need to be?,

I said that simply investing an equal amount in each company (10% in 10 companies in my example) may not be the best approach. Instead, we must strive to invest more of our capital into the Homeruns, as they emerge, and as little as possible into the Distractions and Base Hits, relatively speaking. Investors who are able to buy more of the right breakout companies, can differentiate their portfolios and significantly outperform.

But When Should These Be Bought?

Hypothesis:

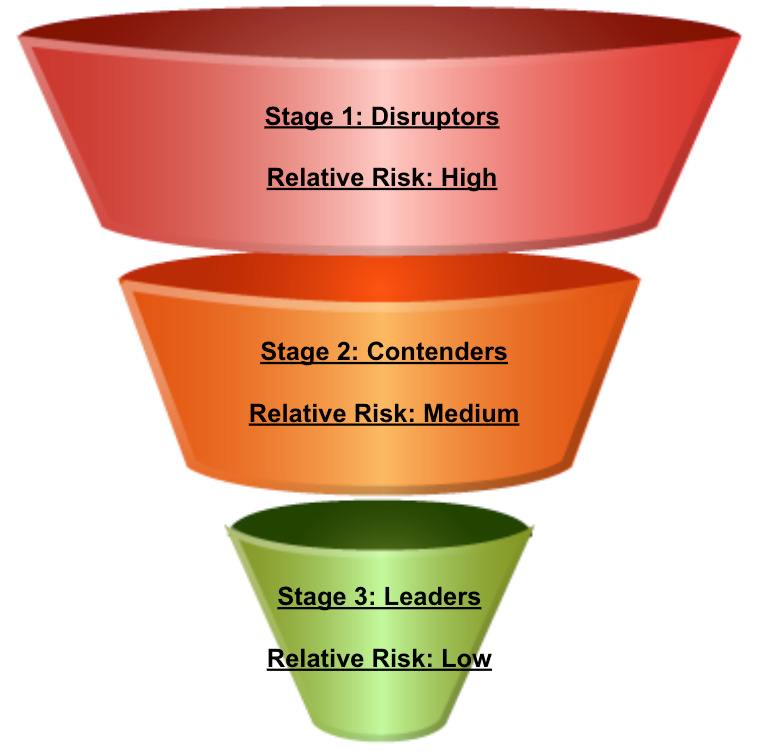

As Mavericks grow and evolve, they go through three stages of development. As they graduate from one stage to the next, they reduce risks inherent in their businesses. Naturally, this reduction in risk warrants higher valuations. Therefore, I believe that buying or increasing stakes in these businesses, when they have been further de-risked, can be a rewarding investment strategy.

This is exactly what good VCs do. They double down at these junctures and add to their stakes in these businesses when risk dissipates. For example, during a Series A financing, investors may be looking for signs of Product-Market fit and the founder’s ability to raise capital, Series B, a repeatable business model, Series C, an opportunity for significant scale, and so on.

Therefore, although we may expect 30-40% of the companies we invest in to turn out to be Distractions, 30-40% Base Hits, and 10-20% Homeruns, we don’t need to invest an equal amount into each of these companies. Instead, we need to keep in mind how much of our capital is deployed at each stage of the risk funnel (below), and what the expected value of returns are at each risk level.

So, how should we deploy our capital?

Let’s explore some approaches.

Since we have 3 Stages in our funnel, we have 7 potential investment permutations to consider:

Leaders Only

Contenders Only

Disruptors Only

Disruptors & Contenders

Contenders & Leaders

Disruptors & Leaders

Leaders, Contenders, & Disruptors

1: Leaders Only

This permutation limits one’s investments to Leaders alone. Building a portfolio of Leaders is perhaps the safest of the permutations. This is because once a company reaches this stage, its business has been substantially de-risked, compared to that of a Disruptor or Contender. I imagine, this is why many investors invest via the “Leaders Only” approach.

I believe such businesses can outperform the market for years, even after it is apparent that they’re dominant businesses. My favorite example of such a business is Google, a business one could have bought for a whopping $100 Billion dollars, and still made a 10X.

That said, we live in a dynamic, competitive and ever-changing world. Therefore, investing in a Leader does not guarantee success. Leaders can and do get dethroned.

2: Disruptors Only

A portfolio investing only in Disruptors undertakes a lot of risk, but in exchange can also have lots of upside. This is one of my favorite stages to invest in because if one is right about even a handful of Disruptors who ultimately move on to become Leaders, the investment outcomes can be quite lucrative.

Unfortunately, since many companies have been staying private longer, having the opportunity to invest early in a Disruptor’s life has been frustratingly difficult for stock market investors. That said, the recent SPAC movement is promising. If SPACs become a common way in which companies go public, then investors may once again have an opportunity to invest early-on in disruptive new businesses.

Having said that, the Public Markets are vast, and sometimes undiscovered companies do go public relatively early in their lifetimes. Shopify, Square, Teladoc and Etsy are good examples of this. So we must remain on the lookout.

3: Contenders Only

After Disruptors have demonstrated initial success, they graduate to Stage 2 to become what I call Contenders. I believe Stage 2 is the most dangerous of the 3 stages. Valuations are high. Expectations are high. And lastly, if they haven’t already done so, Competition is taking direct aim. As a result, investing only in Contenders may in fact be a recipe for failure. Because of the failure rate, the expected value of a portfolio of such companies may not be positive.

As a result, it may be more prudent to wait and buy once it is apparent that a company is no longer a contender, and instead a Leader, that is, to wait until the future outlook of the company is clearer. The Trade Desk is a good example of this, a company that emerged as the leading Demand Side Platform (DSP). Unlike the Trade Desk, there were several of its competitors that didn’t make it, including one the VC firm I worked at had invested in. Lesson learned…I hope.

The best companies are able to defend their turf, continue to innovate and ultimately prove their legitimacy to the world. The hard part about investing in Contenders is that their sources of competitive advantage are usually not well understood, or still taking shape. Therefore, if one can identify these, and build conviction about them, then a company that looks like a Contender to one investor may in fact be a leader to someone else. Something to keep in mind.

4 & 5: (Disruptors & Contenders) OR (Contenders & Leaders)

I find investing in Contenders to be hard. This is because the failure rate of Contenders can be high.

Slack is a good example of this. The company wasn’t able to remain independent. Instead, in order to more effectively compete, it chose to join forces with Salesforce. In this case, our investment outcome was great (~60+% in short order). But that may not always be the case.

Therefore, these two permutations may not be worth the trouble. Perhaps it’s better to invest in the next permutation instead?

6: Disruptors & Leaders

I find that the most powerful investments occur when a company offers both resilience AND optionality.

Amazon was the perfect example, where their eCommerce business provided resilience, while AWS optionality. This turned out to be a superb combination.

Permutation 6 gives us the opportunity to do just that, build a portfolio composed of both resilience (from Leaders) and optionality (from Disruptors).

This represents a classic barbell strategy.

Investors can buy a combination of smaller, innovative, but less proven companies early in their lifecycle in addition to dominant or emerging Leaders of industry.

7: Disruptors, Contenders & Leaders

Again, per the above, since I believe investing in Contenders can be quite hard, Permutation 6 (Disruptors and Leaders) may be a better approach than this one.

That said, if there is one thing I’ve learned about investing, it’s that there are no rules in investing. So if an investor can identify a future Leader while they’re still a Contender, one may in fact do quite well.

So, how much should one deploy at each stage of the Risk Funnel?

Although I have described the different permutations, there are an infinite number of ways to deploy capital into each of the above risk stages.

This is because investing is very personal. The same investment opportunity may look amazing or extremely risky to different people. People have different objectives, experiences, time frames, risk tolerance, personalities etc. All of these affect one’s investment judgement. Judgement, risk perception, and risk appetite can translate into very different portfolios. A person investing only in Leaders may choose to be highly concentrated, and only invest in say 5-10 stocks. On the other hand, someone only investing in Disruptors may end up with 50 stocks. Others somewhere in between. There is no right answer.

Let’s assume we invest in Disruptors and Leaders, but not Contenders. Then,

Expected Return

= Sum of Expected Returns from each Risk Level

= Expected Returns from Disruptors + Expected Returns from Leaders

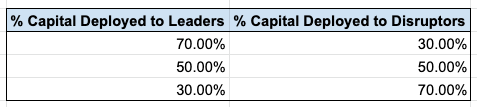

Here are three potential allocations.

Of the three allocations above, the “70% Leaders, 30% Disruptors” portfolio may be the most conservative. It values resilience over optionality.

A ”50-50% Split” is a more aggressive portfolio.

A “30% Leaders, 70% Disruptors” portfolio takes an even more aggressive approach.

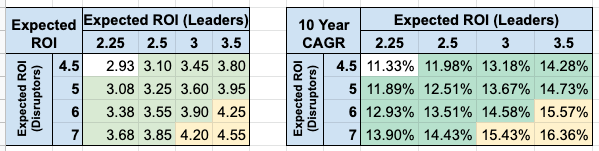

I often hear investors say, they’re targeting 12-15% annual returns. A 12% CAGR implies a ~3X over 10 years and a 15% CAGR implies a ~4X.

With a 70-30% allocation,

below is what’s required to generate those 12-15% returns over 10 years.

Specifically,

Leaders need to generate a 2.5X or better

AND Disruptors need to outperform Leaders, and generate a 4.5X return.

This is a pretty important insight. One must have these numbers in mind when making their investments. (Of course, these numbers would differ with a different allocation)

This also presents an interesting dilemma:

If one can generate a 2.5X with Leaders alone, then a 3X is simply 20% more. If that’s the case, why even bother with Disruptors?

It’s a fair question. Of course, the only reason one would choose to allocate towards Disruptors is if they are indeed confident this adds to their expected returns. Disruptors may provide that extra punch to get to that elusive 15% CAGR threshold. Then again, expecting a 4.5X is quite a demanding requirement. Another approach may be to further concentrate one’s investments in Leaders instead. That may result in better performance. But that may then require a better hit-rate (percentage of investments that don’t lose money). Some people are comfortable with that. Others less so.

As you can see, we could come up with several different portfolio compositions. There is no “right answer”. There are always trade-offs. This is what makes investing interesting (and not easy).

In Conclusion

I believe that buying or increasing stakes in Mavericks, when they have been further de-risked, that is, when they graduate across the different stages of the risk funnel, can be a rewarding investment strategy.

As a result, we must keep in mind how much of our capital is deployed at each stage of the risk funnel, and what our expected returns are at each risk level.

Based on our own allocations, the above table highlights some interesting insights into what our expected returns need to be.

If you enjoyed this article, share it with a friend, they may like it too!

If you’re aware of any books that discuss portfolio composition or construction, do please share it with me.

Thank you and Happy Investing!