Uber TAM: A Case Study + What's Really in a TAM?

I am a fan of the Coffee Can Portfolio, an “Active Passive” approach to investing. The idea is simple: You try to buy a basket of the best stocks you can and let them sit for years. You incur no costs with such a portfolio, and it is simple to manage.

You can track my stock baskets here on my Scorecard.

All high growth companies have one thing in common.

They all say this:

We believe our Total Addressable Market (TAM) is... [Insert Insane Number Here!]

So should we believe them? What’s really in a TAM?

Some investors don't look at the TAM at all. They think it's a completely irrelevant metric. On the other hand, some love to look at the TAM and want to know how realistic it is.

I don’t put too much weight into the TAMs provided. There are two reasons for this:

First, I find that anchoring oneself to a TAM can be dangerous.

And second, optionality can often render TAM Obsolete.

As a result, instead, I try and understand what a company’s end markets look like, and assess whether they are large, growing, or undergoing significant change (this last factor may in fact be the most important). Based on this, I decide whether a company has a large addressable market.

A large addressable market is very important. Recall, we are trying to Invest in Mavericks. In order for this strategy to succeed, we need to benefit from the Power Law of Outcomes. Unless there are severe price dislocations in the market, such outcomes only come to companies with long growth runways ahead (i.e. companies selling to large end markets). As a result, before making an investment, I do need to believe that a company can continue growing for a long period of time. That's where the big returns come from.

Anchoring to a TAM = Bad Idea

I find that anchoring to a TAM can be dangerous.

It’s often easy to point to the current TAM and think it is not very big. Take Google for example. When they first started out, the daily search volume was nowhere near what it is today. Although I don’t recall the last day I didn’t use a search engine, there once was a time when most people didn’t use search engines. Therefore, not only were the number of searchers, and the searches per user relatively small, the types of queries that Google could answer well were also relatively small. All of these components obviously grew tremendously.

As you can see, anchoring to a TAM can be dangerous, especially when investing in Mavericks. Recall that Mavericks are innovative companies that are bringing the world forward. By definition, they are doing things that haven’t been done before. As a result, it can be dangerous to anchor on a TAM based on how the world works “today”, rather than how it will work in the future.

Which leads me to my second concern about TAMs.

Optionality Can Render TAM Obsolete

It’s important to remember that TAM is always changing. Amazon's TAM in 1997 was just Books. What's Amazon's TAM today? Significantly more.

If a company has the ability to launch new products and services in adjacent markets, that can dramatically expand a company's total addressable market opportunity. Therefore, rather than considering a company’s TAM as a static number, determining whether a business has optionality is a far better approach.

Software-as-a-Service businesses tend to do this well. After landing a customer, they often roll out new services. This not only creates revenue expansion from existing customers but also helps them expand their customer base by getting into new verticals.

MongoDB is a good example of this. Last June 2020, I briefly described MongoDB’s TAM expansion potential here.

Uber’s TAM: A Short Case Study

The below shines a light on the two challenges I mentioned above.

Determining Uber’s TAM has always been difficult. In June 2014, Aswath Damodaran, a finance professor at NYU’s Stern School of Business, published an article on FiveThirtyEight titled “Uber Isn’t Worth $17 Billion.” Professor Damodaran concluded that his best estimate of the value of Uber was $5.9 billion, far short of the then valuation of the company.

Damodaran used two primary assumptions for his analysis. The first was TAM, and the second was Uber’s market share within that TAM.

For TAM, he wrote

“For my base case valuation, I’m going to assume that the primary market Uber is targeting is the global taxi and car-service market.”

He estimated this TAM to be $100 billion. For Uber’s market share, he guessed that the maximum market share the company could achieve was 10%. These two assumptions led him to his $5.9 Billion estimate.

As we know, Uber went on to become much more than a taxi-service. Today, Uber’s market cap is a whopping $100 Billion! That’s a 17X difference. Even if you believe Uber is overvalued today, say a generous 100% over-valued, that’s still a 8.5X difference.

Where did Damodaran go wrong?

The mistake Damodaran made was anchoring to a TAM based on how the world used to work in the past, rather than how it would begin to work in the future.

Damodaran assumed that the arrival of a product like Uber will have zero impact on the overall market size of the car-for-hire transportation market. Uber had created a materially better offering. When that happens, one can materially expand the market in the process.

Another example of this is the iPhone.

Steve Balmer, former CEO of Microsoft, famously laughed at the iPhone when it first came out. Here is what he said:

“$500 Dollars?!

Fully Subsidized with a plan.

That is the most expensive phone in the world.

And it doesn’t appeal to business customers because it doesn’t have a keyboard, which makes it not a very good email machine.”

— Steve Balmer

Of course, in hindsight, it’s easy to recognize why Balmer was wrong. But it wasn’t so obvious back then.

This is precisely the trap we need to be careful of when Investing in Mavericks. As I’ve said before, investing in Mavericks is a Venture Capital approach to the stock market. This approach is really about betting on businesses benefiting from “significant changes in the status quo”.

I believe Uber is a Maverick. Uber was re-defining the transportation market, and as a result, had the potential to materially change how that market functioned. Of course, that is hard. It is failure-prone. In fact, failure may even be the most common outcome for such businesses. But as investors in such businesses, we must always ask ourselves: “What can go right if said business succeeds?”

When they do succeed...watch out! That’s where the power law returns come from. This is exactly what Uber did.

Bill Gurley’s Rebuttal

Bill Gurley, Uber’s Series A investor, later rebutted Professor Damodaran’s analysis and suggested that Damodaran may in fact be off by a factor of 25X!

In his article he went on to list out the reasons why anchoring on the Global Taxi market was a mistake. He said three factors would increase the TAM:

The first was what he referred to as a Radically Different (Better) Experience. Uber provided shorter pick-up times, better coverage density than taxis, and frictionless payments. Also, Uber’s dual-rating system where customers rated drivers and drivers rated customers lead to a much more civil rider/driver experience. And lastly, Uber significantly improved Trust and Safety by creating a system that was much more accountable.

Second, Uber enabled a whole set of new use cases. Uber increased use in less urban areas. It provided a rental car alternative, a convenient way for a couple’s night out, and a way to transport kids or older parents. Uber also supplemented mass transit. And lastly, Gurley felt that Uber was a legitimate alternative to Car Ownership.

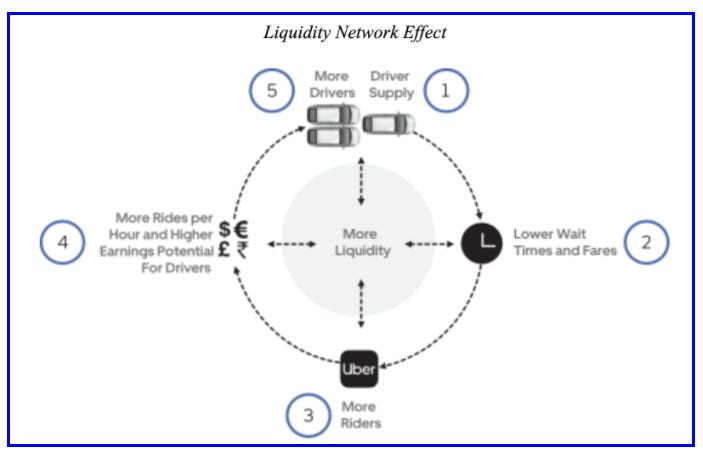

Third, due to network effects, Gurley believed Uber could gain much more that a 10% Market Share. He believed that there were 3 drivers of network effects in the Uber model: Pickup Times, Coverage Density, and Utilization, all of which increased network liquidity.

If you had come across Gurley’s blog post in 2014, would you have believed him?

Interestingly, the above case was made without any consideration for how/if Uber could impact the logistics market or expand into any incremental services.

Meal Delivery is a wonderful example of how Uber successfully leveraged its logistics network for a new purpose in an adjacent market. This foray into meal delivery increases network utilization, and therefore strengthens Uber’s network effect. Uber is leveraging its in-house “logistics-as-a-service” platform to build, partner with and acquire new products to quickly scale new businesses. Postmates can provide general local delivery, Cornershop groceries, and Drizly alcohol. In fact, this is one of the main reasons I purchased Uber stock last September. Per my Scorecard I bought Uber on September 8, 2020. It’s up about ~58% since then. Although I’m pleased with the short term gains, it’s too early to call this a win just yet. Let’s see what the next few years bring us.

The above is a wonderful example of how Uber rendered its earlier TAM obsolete.

In Conclusion

The TAM represents the total pie. Companies however, at best, are able to get only a slice of this pie. But the pie is what dazzles. It is what people remember, because it’s the biggest number in the slide deck.

To me, although a company’s TAM can be an interesting data point, I don’t put too much weight into it. I find that anchoring to a TAM can be dangerous. Plus optionality inherent to a company can often render its TAM obsolete. As a result, instead, I find it more helpful to understand what a company’s end markets look like, and whether they are large, growing, or undergoing significant change. Before making an investment, I do need to believe that a company can continue growing for a long period of time. That's where the big returns come from.

If you enjoyed this article, share it with a friend, they may like it too!

And let me know how YOU assess a company’s TAM.

Thank you and Happy Investing!